Here are the books I read in July, in order, and the words therein that stayed with me:

#28

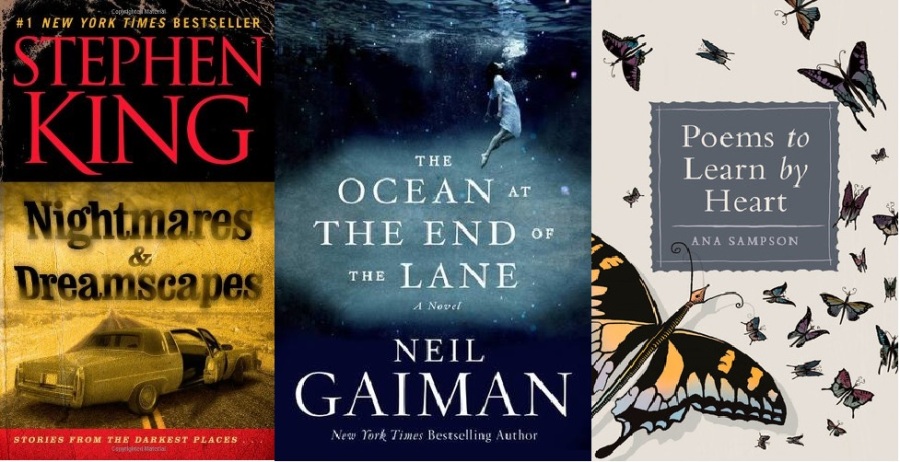

“The worst—for me, at least—is the gnawing speculation that I may have already said everything I have to say, and am now only listening to the steady quacking of my own voice because the silence when it stops is just too spooky.” – Nightmares and Dreamscapes by Stephen King

I have stated before that Stephen King is, in my opinion, the greatest living storyteller, and this anthology continues to reinforce that belief. It is a curious collection of short(ish) stories ranging from the horrific to the fantastic, each of them filled with vividly imagined characters and all-too-familiar places. I particularly loved the melancholy beauty of ‘My Pretty Pony,’ the outright horror of ‘The Moving Finger,’ and the excellent crafting of ‘Sorry, Right Number.’ King’s narrative imagination is so vast, and each story differs so completely in voice and style from the next, that it is hard to imagine all of these stories springing from the same author. And while there were many moments within the stories that made me chuckle or tremble or gasp aloud, the line which spoke to me most deeply actually came from King’s introduction to the collection. Our imagination, he points out, allows us to make leaps of faith and become absorbed in stories, so absorbed that words on a page can frighten and alarm us in a very real way. But far more scary to him, the king of horror himself, is the idea that one day the imagination which allows us to dream up these horrors and fantasies, the imagination which allows us to believe in something so completely for 60 pages, will one day be silenced. The scariest thing of all would be to become irrelevant and detached, to lose our ability to tumble head-first into imagined worlds.

I must say I agree.

#29

“I went away in my head, into a book. That was where I went whenever real life was too hard or too inflexible.” – The Ocean at the End of the Lane by Neil Gaiman

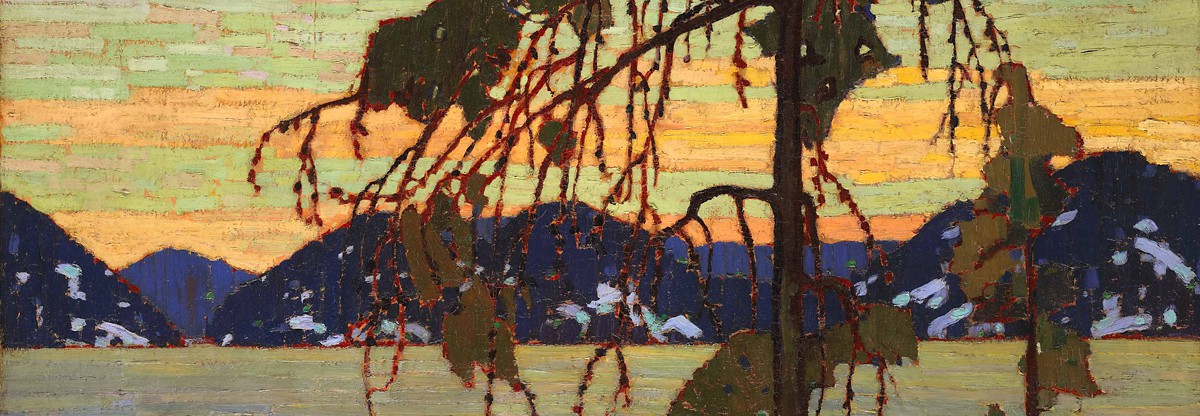

I devoured The Ocean at the End of the Lane in more or less one day, on the shores of Canisbay Lake in Algonquin Provincial Park. Just like last year, the right book seemed to fall into my lap at just the right time in that incredible place. Gaiman’s novel is razor-sharp. Like so many of my favourite stories, it cuts right to the core of some of the questions with which I grapple most every day: the comparative value of youthful wonder and adult knowledge; the question of evil; the nature of the self; the importance of stories in the way we interact with our world. It really is an incredible piece of writing.

One of the reasons I so look forward to my yearly pilgrimage to Algonquin Park is the opportunity to disconnect. The incredible beauty and devastating calm of the forests and lakes do not merely allow introspection – they almost force it upon you. Perhaps any book read there takes on a deeper nature, because the reader is inherently altered by their surroundings; I truly believe, however, that this book was a particularly perfect choice. Gaiman says many things well. So many lines and passages spoke to me as I lay in a hammock between two tall pines, looking out at passing loons floating in deep, clear water. How the goosebumps erupted on my arms when I read, “I wondered, as I wondered so often when I was that age, who I was, and what exactly was looking at the face in the mirror. If the face I was looking at wasn’t me, and I knew it wasn’t, because I would still be me whatever happened to my face, then what was me? And what was watching?” But most of all, I latched on to the simple statement above. Books, like my beloved Algonquin, are where I have always gone when the “real” world overwhelmed. And with books like this one, can you blame me?

#30

“Though I am old with wandering

Through hollow lands and hilly lands,

I will find out where she has gone,

And kiss her lips and take her hands;

And walk among long dappled grass,

And pluck till time and times are done

The silver apples of the moon,

The golden apples of the sun.” – from The Song of the Wandering Aengus by W.B. Yeats

Though this collection did not match, in my opinion, the excellent composition of the Holdens’ Poems That Make Grown Men Cry, it was a nice collection of some of the most memorable verses in English poetry. Few of them were unknown to me, but I think the collection serves its purpose well – to provide a library of poems which are easy enough to memorize and recall from memory, on a variety of topics. Rote memorization is a lost art (though perhaps my grandparents’ generation would say “good riddance”), and I have always admired those who can pull snatches of poetry from thin air to fit the situation. Perhaps I may try to commit a few to memory myself?

Of all the poems in this short collection, Yeats’ was one I had never encountered, and its stirring imagery of young and old love tugs at my heartstrings and tear ducts. Here I have just included the final stanza, but it is worthwhile to read all three.

*****

Seven months down. Five months and 20 books to go! Check back every month for more Words on Words and other thoughts on An Awfully Big Adventure!