Over the past month, I have evaluated four different “Top 100” book lists from four major media organizations:

- TIME’s 100 Greatest Young Adult Books

- PBS’s The Great American Read

- The Guardian’s 100 Best Nonfiction Books of All Time

- Amazon’s 100 Books to Read in a Lifetime

At first, I simply wanted to see how many books I had read compared to lists of books I “should” read; however, in the spirit of being more critical and deliberate in my media consumption, I thought it might be worthwhile to also examine the composition of these sorts of lists. I came up with four data sets to pull from each list which would give me a fairly complete picture of the diversity (or lack) present in each list, and give me insight into the methodology of assembling a “Top 100” style list.

It is worth noting, I think, that none of these are “listicle” or “click-bait” style lists, as you would see produced by viral content factories like Buzzfeed. These lists were put together by news and media organizations who, ostensibly, embody responsible literary journalism. As we will see, that responsibility has been met or missed to various degrees. These lists also represent different genres of written works. I don’t mean to make an apples-to-apples comparison of how “Top 100 Children’s Books” lists are published; instead, I wanted to look at lists from a variety of genres to see how media outlets approach this kind of task more generally.

So, what did I use to evaluate the lists? How did each list fare? And what, if anything, can we learn about our reading and media consumption habits? Let’s dive in:

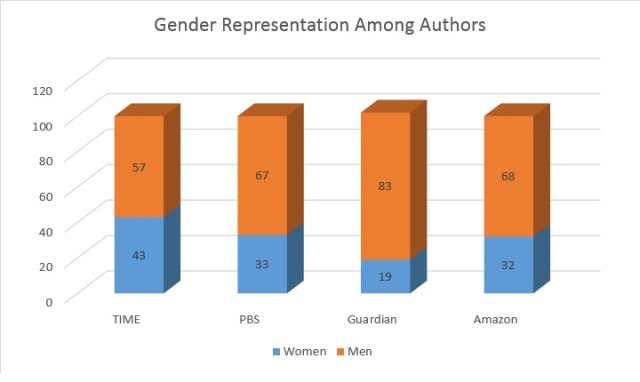

Criteria 1: Gender Representation Among Authors

The first data set I looked at across the four lists was how close they were to gender parity among the authors represented. Even in 2018, none of the four lists featured any gender non-binary authors, so we are strictly speaking male/female. While none of the lists quite reached parity, TIME came closest with 43 female authors. The Guardian, in its list of nonfiction books, had the worst disparity with only 19 women out of a total 102 authors.

How does this compare to gender representation within the publishing industry itself? The number of books published by men and women is notoriously difficult to quantify, primarily because so many books are being published, and there are so many ways to publish a book these days. One statistic that is measurable, though, is how many books by men and women are reviewed by literary journals each year. Vida is an organization for Women in Literary Arts, and they publish an annual study on precisely this statistic. Consistently, men make up an average of 66-70% of books reviewed in major journals like the New York Times Book Review and the London Review of Books. This is not surprising, as the same study found that men held jobs within those publications by roughly the same ratio. This average is also reflected across the four lists I reviewed. It seems that the only place where women outnumber men is in the publishing industry itself, with women reportedly making up 78% of publishing jobs in the United States.

If women make up greater than 50% of the population, why are books by women reviewed (and, let’s be honest, probably published) far less often? It is because repressive systems self-perpetuate. Men have been publishing (and voting and owning property and being paid a living wage and…) for centuries longer than women in Western society. Another study, this one by Tramp Press, found authors submitting manuscripts listed their literary influences as only 22% female – even though 40% of submitters were women. Female authors still find more inspiration from their male predecessors because there are more of them. Just as in every unjust system which has historically placed less value on women, it continues to take time to overcome the imbalance.

One final note: it is interesting that all three articles I found on gender imbalance in publishing are from the Guardian; yet when it came time to assemble their own Top 100 list, they had the worst female representation of the bunch.

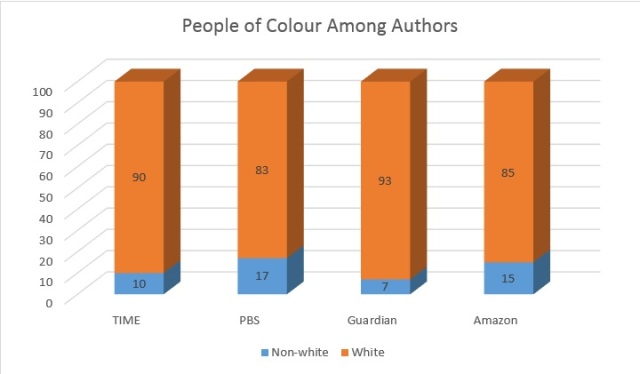

Criteria 2: Racial Representation Among Authors

The same study that found 78% of jobs in publishing are held by women also noted than 79% of those jobs are held by white people. Thus it should hardly be surprising – if 79% of the people making decisions about what gets published are white – that books by people of colour are in shockingly low supply. The lack of diversity in publishing is well documented; a study by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center found that just 8% of children’s books in 2014 were written by non-white authors (the number grew to 12% in 2016). If these four lists are an accurate representation of their respective genres (YA fiction, nonfiction, adult fiction) then the numbers probably carry outside of children’s lit as well.

Leading the pack in the category of racial diversity is PBS’s list for their Great American Read series with a whopping 17 people of colour represented. The Guardian, again the publisher of the widest range of articles on race in publishing, brings up the rear once again with a mere 7. As was the case with the gender disparity, people of colour are fighting an uphill battle against hundreds of years of zero diversity in publishing. They are also disadvantaged by the fact that these lists were published in America and the UK – where at best there is a historical lack of diversity, and at worst institutional and casual racism is at its worst since Jim Crow.

One of the commitments I made to myself at the beginning of the year was to do whatever I could, in my reading and purchasing habits, to support more diversity in publishing. The world is a more interesting, nuanced, fair, and lovely place when you step outside of the bubble of your daily lived experience, and try to understand things from the point of view of another. Stories, poems, words – these things have so much power to change the way we think and the way we understand the world; however, continuously reading stories, poems, and words that reinforce and reflect your own reality will change little. But even that is a privileged observation, because I have never felt there was a lack of stories that reflect my reality.

There is so much to navigate here, with this issue in particular. Everyone – everyone – should see themselves reflected in media. Representation matters. The only way this massive imbalance (that in no way reflects the racial diversity of readers) will begin to get better is if we make diversity a priority. It will take a conscious effort from both readers and publishers to give the spotlight to people of colour. As a white person who very much hopes to publish something, someday, everything tells me to hope for the status quo; things staying the way they have always been gives me a huge advantage by pure dumb luck of my birth. But I do not hope for that. The world is not short of white voices. I hope I have to fight like hell to get something published among a sea of diverse voices. And when it finally happens, I hope it is because I have written something worth reading, not because people who look like me get published 8 times as often.

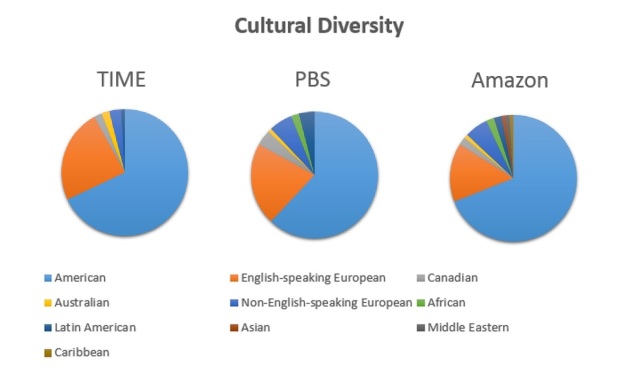

Criteria 3: Cultural Diversity Among Authors

Despite their seemingly global titles (100 Greatest Young Adult Books, 100 Best Nonfiction Books of All Time, etc.), these are still lists assembled and published by American and British media. The curators of these lists have not read every book ever written in every language on earth; their choices are inescapably informed by their circumstances. American and English schools overwhelmingly teach American and English books, and adults generally continue to read what they read when they were young. It takes a conscious and concerted effort to seek out books from outside of your cultural upbringing – they are less available, in many cases both physically (ie- in bookstores) and linguistically (ie- a lack of translations). But titles like “The 100 Best Nonfiction Books We Have Ever Read, and We Grew Up In England” just don’t carry the same weight as “All Time”.

I don’t mean to imply that the compilers of these lists are not widely read, culturally. Amazon’s list presented books from 10 different cultural backgrounds (poorly and broadly defined on my part). But even on the most diverse list, 69% of the books were by American authors. This sort of Americentrism will always exist in American media; in the same way, I am sure that a list published by The Globe and Mail would contain more books by Canadian authors (I would be right). Media is a product of its environment breaking out of the reinforcement loop of promoting American books to an American audience would require a massive shift in prejudice and perception that is, frankly, unrealistic. However, I do think that, in lists like these – particularly from relatively responsible and respectable media organizations like those I featured – there is an onus on the curator to be more thoughtful in the way these lists are compiled.

Assembling a list under a title including superlatives like “The 100 Greatest” or “All Time”, and proceeding to populate that list with books from a single culture, ethnicity, or gender does nothing but perpetuate the echo chamber. As I pointed out in most of the individual reviews, this sort of favouritism towards Anglo-American writing under globalist headings, when not examined and interrogated, sends a single message: of all the books ever written, nearly all the ones worth reading were written by people in two countries. In fact, China published drastically more books per year than any other country, while Great Britain does not publish significantly more annually than Japan. Looking at these lists, you would think Asia has no publishing industry at all.

There are a few ways I can see that publishers of these lists could confront the inherent bias in their compilation: either by being more explicit in their titles (PBS’s The Great American Read does this, to be fair), or else by speaking to why these sorts of regional and cultural biases exist. People in the developed world (particularly in the British and American Empires) have had access to two critical resources essential to publishing that others simply do not have: money and time. Relative wealth and social security, often at the expense of the cultures underrepresented on these lists, enable aspiring writers in America and Great Britain to take the time to write, and to get paid for it. Their publishing industries have thrived, perhaps to excess, because they are in the extraordinarily privileged position of being free to write for a living, if they can. To compose a list that so heavily features books written in the Anglophone “West” without acknowledging the deep-rooted biases that led to the imbalance is unfair to the hardship, beauty, and value in global literary traditions.

Criteria 4: Date of Publication

The final data set I pulled from the lists looked at a different type of diversity. I wanted to see how each list prioritized new material versus what are broadly called the “classics”. I have expressed many times my feelings on the Canadian/American school system’s focus on classic literature. I think there is certainly a balance to be struck – a proper understanding of literature today relies on an understanding of its predecessors – but I think that most curricula today are still far from balanced. Most of the books I read in high school are the same books my parents read in high school; and even back then, they were “classics”. In the same way that Anglo-centric lists create the false impression that the only books worth reading were written in English, “Classic”-centric lists (whether Top 100 lists or high school syllabi) create the impression that the only books worth reading were written over 50 years ago. So, did these particular lists avoid that trap?

TIME’s list of Young Adult books had the greatest percentage of books written since 2000, which makes sense based on the boom that the YA industry has experienced in what we could fairly call “the Age of Harry Potter”. The most balanced list overall, in terms of relative distribution across all eras, was actually PBS’s Great American Read. PBS also gives the most insight into how its list was compiled; they asked 7,200 Americans what their favourite book was, and pulled the results from that poll. Assuming that they used due diligence to ensure a representative sample of the larger US population participated in the survey, it makes sense that the books included would be as diverse as readers themselves, spanning every epoch of (still mostly white, male, and American) writing.

The Guardian’s list of nonfiction appears to be nearly the inverse of the other lists, with 47% of the books on that list being written before 1900. But to be fair to the Guardian list, nonfiction was the dominant form of writing for centuries, perhaps even millennia, before literature and fiction overtook it. Because of this, they suffer a bit from being placed on the same scale as the other lists – the 47% represents a long and varied intellectual tradition that cannot easily be compared to the 20th century fiction heavily features on the other three.

So what?

What does any of this matter? Was it worth the excessive number of hours I put into all of this? Can we really learn anything of use from examining lists? I think we can. Here are my takeaways, and feel free to add your own (or your criticisms of mine!) in comments:

- We live in an echo chamber. We read what is familiar to us, which makes books (and poems and articles and movies and television shows) that represent our established point of view more successful. The more successful and pervasive a piece of work becomes, the more likely it is to end up on a list like this – where it is referred to still more consumers, making it more popular and further reinforcing the status quo.

- Representation matters. Today, in 2018, we still are not doing enough to ensure that everyone, regardless of how they identify themselves, sees themselves celebrated in literature and popular culture more broadly.

- Motive matters too. Brittany at Perfectly Tolerable, who originally brought the Amazon list to my attention, made a great point in the comments on that post which I had never considered. Another important element to look at is whether the publisher of the list stands to gain anything by what they include on the list. In the case of three of the lists, the answer is presumably (hopefully) no. But in the case of the Amazon list, Amazon is A RETAILER OF BOOKS. So of course they stand to gain from publishing a list titled “100 Books to Read in a Lifetime,” and then including purchase links to the Amazon page for each and every one of those 100 books.

- It is worth the effort. As I have said, I made a personal commitment to read more diversely and more conscientiously this year. This exploration of the way that the media encourages people to read (ultimately, these lists serve as recommendations) has only served to harden my resolve to do what little I can do to find voices and works that challenge my point of view instead of reinforcing it. Reading comfortably only promotes complacency, and I will not be complacent.

One more thing…

Of course, there is one more thing – the thing I set out to do in the first place. I was inspired by Thrice Read, when I started this whole thing, to take a look at my own reading history against these lists. How did I do?:

- TIME: 43/100

- PBS: 54/100

- The Guardian: 28/100

- Amazon: 40/100

Great stats and great post! That is a lot of data and it probably took you a long time to compile it all, so kudos to you!

At first I thought that it wasn’t really fair to compare the lists based on the statistics about the authors, because you can’t really judge a novel by its author. And, if I had to guess, the list makers probably didn’t even look at if the author was male or female. But my immediate second thought was that if you were judging books solely based on the book does that mean men write better books than woman? Is that why more of the books were written by men? I refuse to believe that, so I basically just refuted my first thought. I think this is an issue more with a society as a whole then an issue with the creators of the lists. Like you mentioned, more books are published by men and I think that is where the issue leads. Its a problem in publishing as a whole, not necessary with the list writers.

One thing I thought was super interesting was that the guardian had the most pre 1900 books and the least amount of female authors. If I had to guess this is a direct correlation. If you compare just the pre 1900 from each list with the gender of the author what percentage is male? (do you still have the stats handy? would it be hard to do that?) I wonder if it would be similar for all the lists? Pre 1900 was a male dominated society so it wouldn’t surprise me if most of the books were written by males.

LikeLike

Pingback: Resolutions Revisited – An Awfully Big Adventure