Growing up within driving distance of North America’s third largest metropolitan city, there are many people who, when asked “where are you from,” just say “Toronto”. It is easier that way. Rather than having to explain where Guelph is in relation to the Big City, and where your small town is in relation to that, you just say you’re from Toronto. As urban sprawl has continued to consume more and more communities into the “Greater Toronto Area,” it is no longer that inaccurate either. And besides, chances are the person you are speaking to was just asking to be polite – they likely don’t care all that much anyway. Of course, other communities in the region are beginning to make a name for themselves outside of the Ontario bubble. Someone from my small town nowadays may well say they are from Waterloo, which has become known for its growing tech and startup communities.

I am not from Toronto. I am not from Waterloo. I am not from Guelph.

I am from Fergus.

Being from Fergus is as essential to who I am as my name, or the colour of my eyes, or the way my voice sounds. Fergus made me. I am not just from Fergus; I am of Fergus. When my parents moved us in a few weeks after I was born in 1991, Fergus was barely more than a village of 8,000 people. In the 27 years since, the population has more than doubled (more than 20,000 at last count), and I have grown with it. I haven’t lived in Fergus full-time for a number of years now – first leaving for school, then work, then marriage – but I still feel daily the impact that growing up there had on my personhood.

I would like to take you on a tour, if you’ll come. Not a tour of Fergus, per se – though there are some excellent historical walking tours available if you are ever in town. I want to take you on a tour of my Fergus – the Fergus of my memory. I will do no fact-checking, present no history nor anthropology. If you are interested in those sorts of things, the town seems to have a fairly complete Wikipedia page. My goal is not to educate or drive tourism. This is not a list of Places To Stay or Things To Do. This is my hometown – the one that made me who I am – the way I remember it.

This is where it all began. Philip Court – the street I grew up on. The trees are bigger now. Our first house is just down the road, on the right. From here, my universe expanded. First our house, then the yard, then the street, the neighbourhood, the town itself. There’s never traffic on a road to nowhere, so my brother and I were safe to play up and down the street with the kids of the other young families who had all moved in together as development was completed. In the winter, I can remember the plow piling snow on the raised circle in the middle of the court, creating a mountain beyond our wildest imagination. Today, kids are probably discouraged from tunneling into large piles of snow, for fear of collapse; but back then, we turned that mountain into an anthill of caves and passageways, and stayed out until the lights came on. I didn’t learn what it was to be a neighbour from Mr Rogers; I learned it here, where everyone knew and looked out for one another.

This walking trail passes by the old neighbourhood. At some point, it runs (or ran, once) through a dense thicket of trees and brush. That section of the path may have run all of 20 metres from end to end. Based on the omnipresent trash that littered the spot, it was probably a popular hangout for teenagers at the time; I don’t think I was ever there at night to find out for sure. But whenever we walked as a family, we insisted on taking the path, so we could walk through this magical fairy forest just down the road. Most of the stories and games we imagined as kids can find their roots among those trees.

This is the church where I was baptized, and which we attended every Sunday until it got to be too small and a new one was built. The church parking lot was a social hub; here we planned many impromptu sleepovers, sprung on our parents after mass and completely throwing off their Sunday plans. One Sunday a month, there were cookies in the parish hall. I always thought it was a little spooky that there were unmarked pioneer graves nearby.

Of course, the majority of my waking hours growing up seemed to be spent at school. My mom even taught here for the first couple of years, until my second brother was born and she decided to take some time off with three (eventually four) young kids at home. I could tell a million stories of friendships that began here (and continue to today), or teachers whom I idolized (and still do), or of course the lessons learned (and some forgotten); I was undoubtedly and indelibly shaped by all of these. My most vivid childhood memory took place here, though, and had little at all to do with school.

I remember with picture-perfect clarity a morning over 20 years ago – I must have been in kindergarten or shortly thereafter. My dad drove me to school, and I did not remember until we pulled into the parking lot that I had show-and-tell that day. There was no time to go back home and find some precious item for me to share. My dad, being resourceful, pulled a large photo plaque out of the back of the car. It showed a mountain slope covered in fresh, powdery snow; skiers had descended the mountain in pairs, carving perfect patterns of criss-crossing curves down the steep incline. It was an interesting photo, and my dad explained how it was created and offered it to me to show the class. I said thanks (or at least I hope I did) but declined. I would just tell my teacher I had forgotten, and bring something the next time. I said goodbye, and immediately felt a wave of devastation wash over me as he drove away. I felt ashamed and overwhelmed with sadness that I had turned down the picture. It suddenly occurred to me that it may have been my dad’s prized possession (it wasn’t) or something he was really excited to share with me (I’m pretty sure it was just quick problem solving), and I had rejected it out of hand. I may have been 6 at the time, but I can still feel the dread and shame I felt the rest of that day that I may have made my father sad. I still get a lump in my throat writing about it now. I think about that morning more often than is believable. I have never talked to him about it – I don’t even know that he would remember. But it is seared into my memory like a brand. That one story probably says more about me than anything else I will write here.

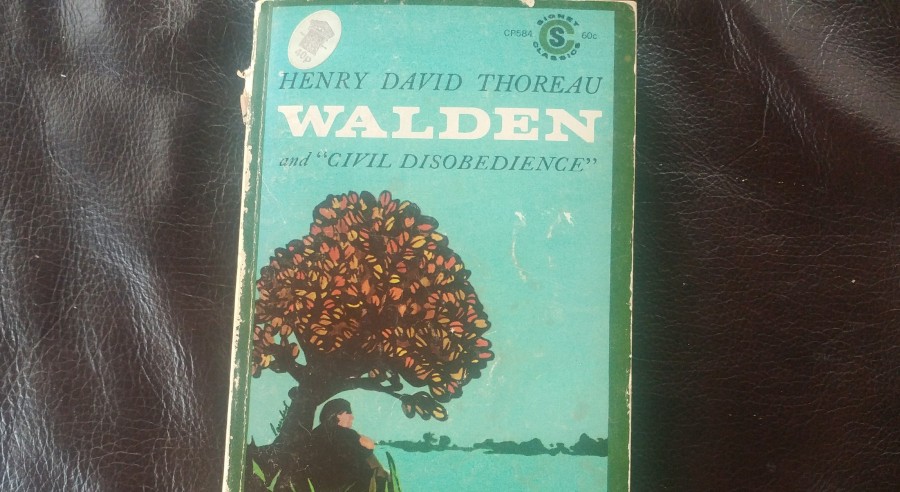

The first place I can ever remember walking by myself (besides school – and the first time I walked there alone I believe I got lost) is the library. They have remodeled the inside since I moved away, but the outside is still the same; perks of being an historic landmark. The library was air conditioned, which our house never was. I remember walking downtown in the morning on a hot summer day to find a book (or six), and not wanting to leave the cool oasis of the library. I would sit and read an entire book in an old leather chair through the height of the afternoon heat, and then as the evening cooled off I would check out the rest of my stack and walk home. It is a testament to both my parents and Fergus itself that in those days before cell phones, if I told my mom I was going to the library and then didn’t come home for hours, there was never any panic. At least none I knew of.

This old foundry building used to house the Fergus Market. It has been converted into self-contained shops now, but back in the day it housed wonders. I have nothing against the current tenants of course, but to my knowledge none of them sell pewter wizards or steam-emitting dragons or farm-fresh meats, or that holiest of grails: hockey cards. Somehow, the farmer’s market in our small town was home to not one but two collectibles vendors. I don’t ever remember having a formal “allowance” like some kids have – but there were few things my parents could leverage to motivate us more than a trip with dad to pick up a few packs of hockey cards, and spend the rest of the day trading, sorting, and admiring. My cards are still at my parents’ house (much to their chagrin) and will likely hit Kijiji soon. But the market is also gone, so it’s alright.

Of course, even the most idyllic of towns has an insidious side. In later grades, my friends and I were too old to take the bus to school, so we rode our bikes. I remember one day discovering that my bike, which I had left outside of the garage the night before, had been stolen. We never found it. In the meantime, I still had to get to school, so I rode my mom’s bike instead. One day, as my friends and I raced down this hill on the way home, the right pedal fell off. I remember time standing still as my forward momentum shifted sideways and I fell to the road, leaving most of the skin of my knee behind me on the pavement. The pain was agonizing, as was the dread of telling my mom I had broken her bike. My friends walked with me the rest of the way home as I bled into my sock. They are still among my closest friends today.

I wrote a few months ago about visiting Roxanne’s Reflections, the local bookstore, for the last time before it closed. I won’t go into it again here – the sadness is still close to the surface. I drove past the other day – the space is now home to the reelection office for the local Progressive Conservative candidate in the upcoming provincial election. He’s a neighbour of my parents, and by all accounts a gentleman. The books are all gone, though.

Second best for second last: my second home, the Fergus Grand Theatre. It got a facelift recently, restoring some of its original glory; to my eyes, it has never looked better. When I was nine, my mom signed me up for the local children’s drama club. This is one of a handful of truly pivotal moments around which the rest of my life orbits. I played basketball growing up, but I never dreamed of playing professionally, or even in college. But from the moment the stage lights hit me for the first time in this 250-seat theatre in Fergus, I was convinced that nothing else would ever bring me joy. Time, money, and life have a way of sobering dreams – I didn’t end up going to school for acting, I chose jobs over shows, and eventually I came to accept that performing was probably in the past for me. A few years ago, things came full circle as I got to return to the Grand to play Peter Pan, the role of a lifetime for me. If I never do another show, I will be happy knowing that my last play was that one, back where it all began.

The last stop on a tour of my Fergus is here, on a small rock shelf beside a waterfall. This is where I proposed to my wife, Angela. She fell in love with Fergus as I fell in love with her; and even without the rose coloured glasses of sentimentalism, she loves it for so many of the same reasons I do. We hope, one day, that our lives will lead us back here as we look ahead to a family of our own. It seemed fitting, when I thought about how I wanted to ask her to marry me, that it should be here. In a way, I had shown her myself by showing her my Fergus. I was saying, “Here is where I’m from; here is who I am.” We were married a year and a half later, at the new church they built to replace the one that was too small.

I am not from Toronto, or Guelph, or Waterloo. I am from Fergus. To walk in my shoes, you have to walk here. It is changed and unchanged, timeless and yet intrinsically tied to a very specific time in my life. You can no longer grab a scoop of ice cream at the Cherry Bomb, or play 5-pin at the Fergus Bowling Lanes, or swim in the old outdoor pool; but those things existed, once, and still do for me. Fergus is my hometown. Maybe it’s like yours, maybe it isn’t. Maybe it was exactly as I remember, maybe it wasn’t. But when I hold a mirror up to that town, I see myself looking back.